I started this project interested in exploring B Corporations and Benefit Corporations, two similar for-profit business structures geared toward social good rather than simply profit maximization. Specifically, I wanted to investigate how sustainable these social business structures are in a capitalist system built around profit maximization and stockholder returns.

First, a bit about B Corporations and Benefit Corporations:

People often confuse the two, or at least don’t fully understand that there is a difference. While both structures were created and promoted by the same Philadelphia-based non-profit called B Labs, there are distinct differences between them.

B Corps

B Corps are for-profit businesses certified by B Labs as having social and environmental objectives above and beyond profit maximization. B Labs describes B Corps as being to business as Fair Trade is to coffee or LEED certification is to buildings. The “B” in B Corps stands for “Benefit”, though it is always abbreviated as just a capital B, probably to avoid confusion with Benefit Corporations, however unsuccessful drawing that distinction has proven to be. There are reportedly 2,100 certified B Corps in 130 countries, with companies as varied as coffee roasters to socially minded technology platforms like Etsy.

Becoming a B Corp

B Corp certification is contingent upon a three step process. First, a business needs to complete an Impact Assessment in which they rate their own performance on sustainability, employee wellbeing, and community engagement. Businesses must score 80 or higher out of 200 to be certified.

Once the impact assessment is completed, whoever completed the Impact Assessment has a phone screening with a member of the B Labs staff and then must submit supporting documentation to back up a randomly selected section of the assessment.

If approved, the business must pay certification fees ranging from $500-$50,000, depending on earnings and amend their articles of incorporation to incorporate social and environmental objectives in addition to profit making. Lastly, the business must sign a “Declaration of Interdependence”, asserting their commitment to working towards a common good. To remain certified, businesses must repeat the certification process every 2 years.

Benefit Corporations

A Benefit Corporation is an incorporation structure legally accepted by 33 US states. Benefit Corporations function just like C Corporations and the process for incorporating (or reincorporating) as one is very similar. The major difference between a C Corp and Benefit Corporations is that a Benefit Corporation’s articles of incorporation must contain language describing the business’s pursuit of a public benefit such as supporting a local community or the environment. Like B Corps, B Labs invented the Benefit Corporation structure and managed lobbying efforts to get if officially adopted as an accepted corporate structure in the 33 US states that recognize it.

Becoming a Benefit Corporation

The process of becoming a Benefit Corporation is actually easier than becoming a certified B Corp. Interested companies, be they startups or established ones, first create or amend their governing documents to include language about their objective to create a public benefit in addition to producing shareholder returns. After that, most states require Benefit Corporations to file annual benefit reports. That is, all states but Delaware. Being that Delaware is the leading domicile for US corporations, including 66% of Fortune 500 companies, it’s not surprising that only 10% of Benefit Corporations publish annual benefit reports.

Motivations

My reason for choosing this topic is deeply personal: most of my professional career has been spent at companies founded on a great social mission, but that were ultimately unsuccessful because their founders didn’t pay enough attention to sustainable business practices. In retrospect, going into this assignment with that motivation was problematic, but not without merit either. My suspicion was supported by the struggles of one of the most recognizable B Corps on the planet: Etsy.

Etsy was a founding member of the B Corp movement and was the first to be traded publically when it filed its initial public offering (IPO) in 2015. Since IPOing, Etsy’s stock has plummeted.

Though their year-over-year revenue has increased, their net income (the profit they generated from their operations) fell because of increased spending on operations, employee benefits, and external social programs, many of which were what drew consumers and sellers to them in the first place. Since late 2016, members of their board and activist investors have been calling for a shake up at the company, either through a sale or through layoffs. This year, Etsy chose the latter option, laying off 15% of it’s staff including its CEO.

Amidst the layoffs and other austerity measures, Etsy was grappling with whether to maintain it’s B Corp status. In Delaware, the only way for publicly traded companies to meet the legal requirements for B Corp certification is to reincorporate as Benefit Corporations within four years of going public. Etsy’s board and new executive team opted to not make this change and consequently lost their B Corp status in November. In my mind, Etsy’s struggles fundamentally challenged the viability of the B Corp movement as a sustainable business practice.

Towards A Prototype

Based on my past experiences and Etsy’s very public troubles, I had a hunch that social businesses, particularly B corporations and Benefit Corporations, generally struggle to balance their social missions with the need to turn a profit. After all, a business needs to spend money both to make money and to do good, but only one of those activities replenishes their coffers and leaves funds to pay back investors (and creditors) in a for-profit model.

With this in mind, I pushed ahead with my research.

For my 7 day practice I wanted to simulate the challenges a business might face when tracking it’s impact. Over the course of a week I tracked every piece of trash I generated and kept a public record on Tumbler. This taught me a lot about how focused and diligent one needs to be to ensure one is mindful of one’s impact. I also gained insights into the waste practices of the company I worked for. A full overview of my 7 day practice can be found here.

To further my investigation, I spoke with Sean Cullen, Uncommon Goods’ benefit administrator. Uncommon Goods was a founding B Corp along with Etsy. According to Sean, doing good is built into the fabric of UG: they are very selective about the products they sell and creators they partners with, ensuring sustainable sourcing practices and small batch production are at the core of their marketplace. They have to make a conscious effort to prioritize responsibility alongside profit and work hard to balance their benefit programs with profit generating operations. I also reached out to Etsy and Warby Parker, but never heard back them. I had a call scheduled with Kickstarter’s Benefit Administrator (the are a Benefit Corporation), but she quit a few days before we were scheduled to speak and cancelled the call before we could have it.

After this I hit a wall…

It turns out that most B Corps and Benefit Corporation are private. This makes it extremely difficult to find objective information about the performance of these businesses. The only way to get this information would be to speak directly to the companies themselves, but those I reached out to were understandably cagey about this information, if they replied at all. To make matters worse, the little performance information that is available comes straight from B Labs, the creators of B Corp/Benefit Corporation, who have a vested interested in presenting a positive image of their member companies to the world. Most of the data I could find from B Labs pertains to their member company’s performance on impact criteria like environmental sustainability and employee happiness, not on financial sustainability. To be fair, that data painted a very positive picture.

While struggling with what to do next, I also realized that perhaps I was chasing my own tale, so to speak. After speaking with Marina, I came to the conclusion that I was spending my energy looking to validate my suspicion rather than objectively researching the topic.

I’m still very interested in the plight of social businesses in a capitalist system, but rather than focus squarely on B Corps and Benefit Corps, I wanted to devise a fun, informative way to investigate the compromises inherent in the pursuit of a sustainable business. Specifically, I wanted to explore the implications of these compromises on social businesses such as B Corps and Benefit Corps, but also encompassing non-profits and mission driven C Corps.

I came up with a desktop roleplaying game. The game is called Founder and in it players found and sustain new businesses. My goal in devising this game is to demonstrate the compromises inherent in running a business, particularly a social business, in a fun and engaging way.

Founder, The Game

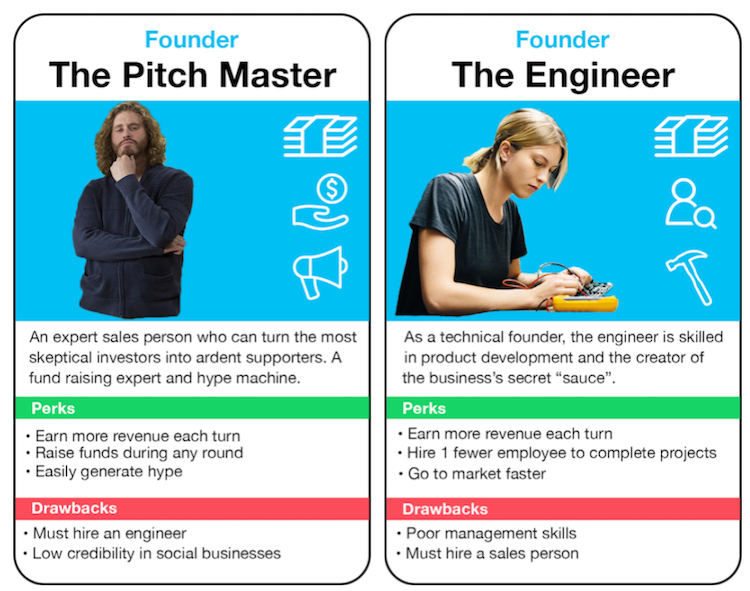

Founder is played by 2-5 players who build their game decks by choosing a type of founder they want to be and the type of business structure they will implement. Founder types include a sales person, a technical founder, a young idealist, a veteran startup founder, and a talented college dropout.

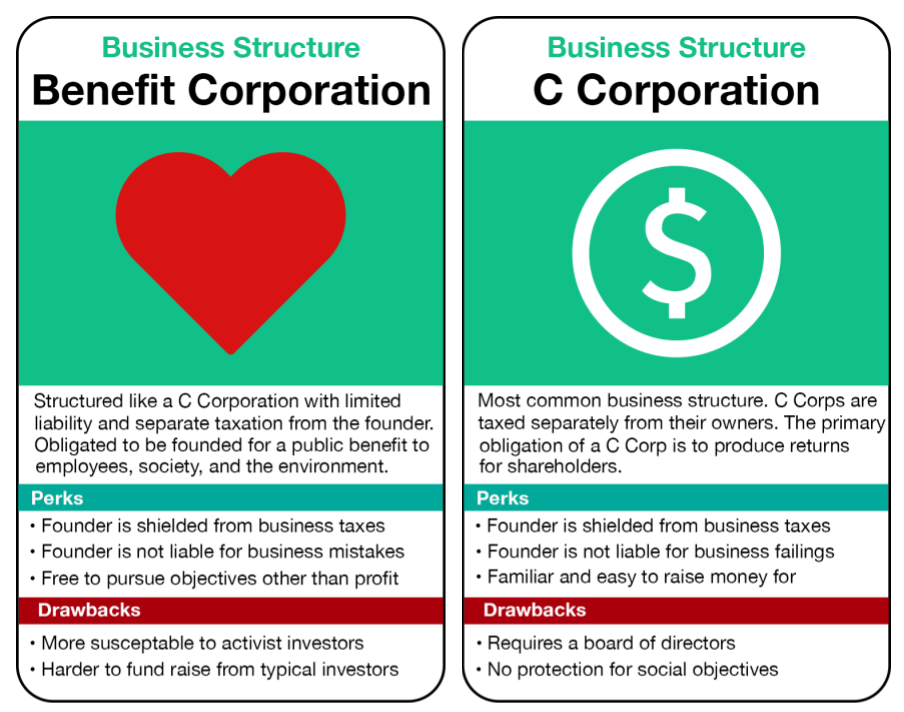

Next the player chooses the type of corporate structure they want. Players can choose between C Corp, Benefit Corp, non-profit, or sole proprietorship. I chose these structures because they are the most distinct, though the game could be expanded to incorporate LLCs and partnerships as well.

The player’s goal is to conserve cash and not go bankrupt before the game ends after 20 rounds of play. To avoid bankruptcy, players must grow their reserve of income tokens. They start with 3 and gain more by building and selling products, raising money, and receiving donations.

Resource cards have a cost, so players have to use their income tokens wisely. Players have the option to acquire and play resource cards that grow their business, make money, or do good for the world. Benefit Corporations and Non-profits are required to do good at least once every 3 rounds.

Lastly, event cards are played at the beginning of every round, disrupting the players plans just as events like taxes, lawsuits, employees quitting, and more come up when running a real business. The goal is that through forcing players to consider how to maintain income while facing externalities, the player will learn the challenges of each business structure.

Takeaways

There is a lot to unpack here.

The most obvious takeaway pertains to my investigation of B Corps/Benefit Corporations themselves, namely that there simply isn’t enough objective information about them. If I was to take this project on again I would firstly need more time and secondly need to approach it like an investigative journalist, rather than as a research-based artist (not that I’m claiming to be the latter). In retrospect, this is more of a professional research project than an assignment. I guess the lesson there is to only bite off what one can chew…so to speak. To that end, I should have attempted to line up my experts much sooner. I don’t know if that would have resulted in a better response rate, but I could have at least had more opportunities. Interview-based research seems similar to sales: it comes down to a numbers game. You want high quality interviews, but you need a lot of them to be successful.

Another big takeaway was to be mindful of one’s own biases. If I’m being honest with myself, I took on this project almost as a vendetta. I have been burned by businesses claiming to do good, so I wanted to validate my hypothesis that all do-good businesses have a dark side. Whether or not that is true remains to be seen, but I realize that my research was more about finding personal validation than actually exploring my topic. I thank Marina for helping me recognize this; it’s something I will be more mindful of going into thesis next semester.

Lastly –and building on my comment about biting off what one can chew– designing game mechanics for a desktop RPG is way more involved than I anticipated. It definitely requires more time and commitment than the 3 weeks I gave myself, especially when juggling other finals. Read the mechanics for games like Magic the Gathering or Munchkin and you’ll see that there is a lot more under than hood than a collection of cards.

Overall, the most useful bit of feedback I received on this project was to be wary of it being a straight-up validation of my bad feelings towards social business models. Ultimately, the mechanics I laid out, though admittedly in need of work, make it difficult for a social business to succeed compared to a profit-maximizing one. A large part of that can be attributed to me baking my bias into the structure of the game. In the end that makes the game just an “ahah” validation exercise for my suspicions, rather than an objective exploration of what is truthfully a very complex and well meaning area business.

All in all, this was a great exercise in a great class and an opportunity for me to learn a lot about how I conduct research. For those who are curious, my full presentation is embedded below: